Poetry & Grief

The “Poetry & Grief” thread of The Entangled Bank grows out of my experience helping care for the dying, first with loved ones and more recently as a hospice volunteer. I had already lived half a lifetime immersed in poetry when I spent several months caring for my father as he died of congestive heart failure, and yet I think of those days and weeks as the first time I experienced the profoundly consoling connection between a poem on the breath and the mystery of loss in the heart. And that is why I have included here “A Good Day’s Work,” an account of my last morning with my father, adapted from the journal that I kept in that summer of 1995.

But really, the origins of “Poetry & Grief,” like the origins of grief itself, go back to childhood and to my first experience of poetry as a living thing, a savor of sounds, a pouring from the vessel of the brooding heart, an awakening of the senses in the breath’s delay in song. Poetry’s beyondness was already there for me in the voices of A.A. Milne’s Now We Are Six:

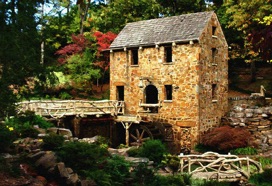

There’s wind on the river and wind on the hill...

There’s a dark dead water-wheel under the mill!

I saw a fly which had just been drowned—

And I know where a rabbit goes into the ground!

It is true that (as the poet Robert Pack’s college professor told him) “Poetry allows us to face with grace and dignity the fact of our death." But this gift comes less from what the poem says than from the broad margin of what it does not say and from the way it feels on the breath. There is a vein of overtly consolatory poetry that ought to be allowed to bleed out and go forever silent– the kind of poem that hits me over the head with sentimentality and shuts me down with answers. A truly consoling poem is all about the questions– the troubling heart, the feelings for which we have no words. And it approaches these things stealthily, indirectly, sparingly, lovingly, as if they were wild creatures always just disappearing in the play of light and shadow in grief’s wilderness. “Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” as Emily Dickinson reminds us.